This site looks much better with JavaScript turned on. For the best experience, please enable JavaScript and refresh the page.

A fantastic flight in perfect weather over Southern England in August 2016.

The flight

Not really a holiday, but nevertheless a fantastic day out. Berni, an old pal of mine with a Private Pilot's Licence, offered to take me on a flight over southern England in a hired Cessna 172 light aircraft. We were both interested in flying over the site of RAF Warmwell, where my dad was stationed in World War 2, and he decided to take in a few other landmarks en route.

His route took us initially west from Booker Airfield near High Wycombe, then south over the Thames, Surrey heathland, Farnborough Airport, Langstone Harbour, Portsmouth Harbour, then over the Solent to Ryde on the Isle of Wight, cutting across the northern part of the Island, passing just south of Cowes, to Yarmouth, Bournemouth, Poole Harbour and then a few circuits around the area of RAF Warmwell. From there we headed north, with a good view of the Cerne Abbas Giant, before landing at the lovely Compton Abbas airfield for a leisurely lunch outside in the sun. After lunch, we took off again and headed over Stonehenge, Avebury Ring, Silbury Hill, Uffington Castle, then via Didcot Power Station back to Booker.

We were incredibly lucky with the weather on the flight - the morning was absolutely still, cloudless, with perfect visibility - we could see for twenty miles. Most of the time we were flying between 1000 to 3000 feet up, so we had a fantastic view of some of the areas I know well. I did a lot of sailing in and around the Solent and Poole Bay in the '80s, and it was great to see so many familiar landmarks from above instead of at sea level.

RAF Warmwell Q-Site

My father was a Leading Aircraftman (LAC) in the RAF in World War 2, stationed at RAF Warmwell on the Dorset

coast,

right opposite the D-Day Normandy landing beaches. He and a corporal manned the base's dummy

airfield ("Q Site") at nearby Winfrith Heath. I was immensely proud that he was Mentioned In Dispatches

twice (see press cuttings, right), for carrying out "duties of a secret and dangerous character" in

1944 on the dummy airfield, the sole purpose of which was to attract Luftwaffe bombs down on themselves

instead of the real airfield. Some

of the stories he told me (see the next section below) gave me goosebumps as

I realised how lucky I was to be alive.

My father was a Leading Aircraftman (LAC) in the RAF in World War 2, stationed at RAF Warmwell on the Dorset

coast,

right opposite the D-Day Normandy landing beaches. He and a corporal manned the base's dummy

airfield ("Q Site") at nearby Winfrith Heath. I was immensely proud that he was Mentioned In Dispatches

twice (see press cuttings, right), for carrying out "duties of a secret and dangerous character" in

1944 on the dummy airfield, the sole purpose of which was to attract Luftwaffe bombs down on themselves

instead of the real airfield. Some

of the stories he told me (see the next section below) gave me goosebumps as

I realised how lucky I was to be alive.

After the war, the site was closed, and then, crazily, handed over to the UK Atomic Energy Authority, who built Winfrith Nuclear Power Station on the dummy airfield site. The construction process was frequently interrupted by the discovery of some of the unexploded high-explosive bombs (described as 'Ux.H.E.' in the letter below) that had rained down on my father!

This is an extract from the community web site of Winfrith Newburgh and East Knighton, September 25, 2016 (unfortunately, this blog page no longer exists):

"My name is Don O’Donnell, I was Foreman Carpenter on the construction of Atomic Energy Station at Winfrith Heath, in 1956-7, the Groundworks and Deep drainage, work was frequently being interrupted by underground explosives, and the Bomb Disposal Squad, (BDS), were almost full time on site, can’t remember any serious incidents."

The nuclear power station buildings are no longer used and are being decommissioned and demolished.

Keep scrolling down for RAF documentation of what my dad experienced (I hope I don't get into trouble for revealing a "Secret" document !) Note that this letter was copied to "Air Ministry, Col. Turner's Department". This was Colonel John Fisher Turner, who masterminded the huge campaign of illusions to fool the German High Command. The Q Sites were just one aspect of his Department's efforts. There's more information here, here, and here (you need to scroll down to the paragraph that starts "The latest addition to Royal Asiatic Society’s catalogue...")

The letter also mentions "Lt. Sampson of Flying Control, U.S.A.". This was because the Americans took over control of the airfield during the run-up to the D-Day landings (note the date on the letter). Remember that RAF Warmwell was on the south coast of Dorset, right opposite the Normandy beaches, so was considered vital for air support on the big day and afterwards.

Dad's Q-Site stories

First, some background:

Most WW2 RAF airfields were protected by a dummy airfield ("Q-Site"), which was created in order to attract bombs down on itself, instead of the real airfield three or four miles away. My Dad manned the RAF Warmwell Q-Site, along with a Corporal – just the two of them. The Q-Site consisted of many hectares of unused heathland (well, unused by humans), requisitioned by the Ministry of War, to the east of the real airfield. Luftwaffe bombing raids were always at night – they had learned the hard way that their bombers would be heavily attacked before they even crossed the South Coast during the day. The idea was that, when the Luftwaffe came over on a night bombing mission, they would be detected by the secret radar installations (see "Chain Home"), all the lights at the real airfield would be turned off, and the Q-Site would be instructed to turn their lights on.

These lights were laid out in a convincing copy of the real airfield’s lights – with landing lights, runway lights, taxiway lights, perimeter lights, lights from buildings on the airfield, and so on, all jury-rigged by running cabling across the heathland to the lamps.

The Q-Site crew had a concrete air-raid shelter / Control Bunker as their

Control Centre – from there, they controlled the switchgear that turned the

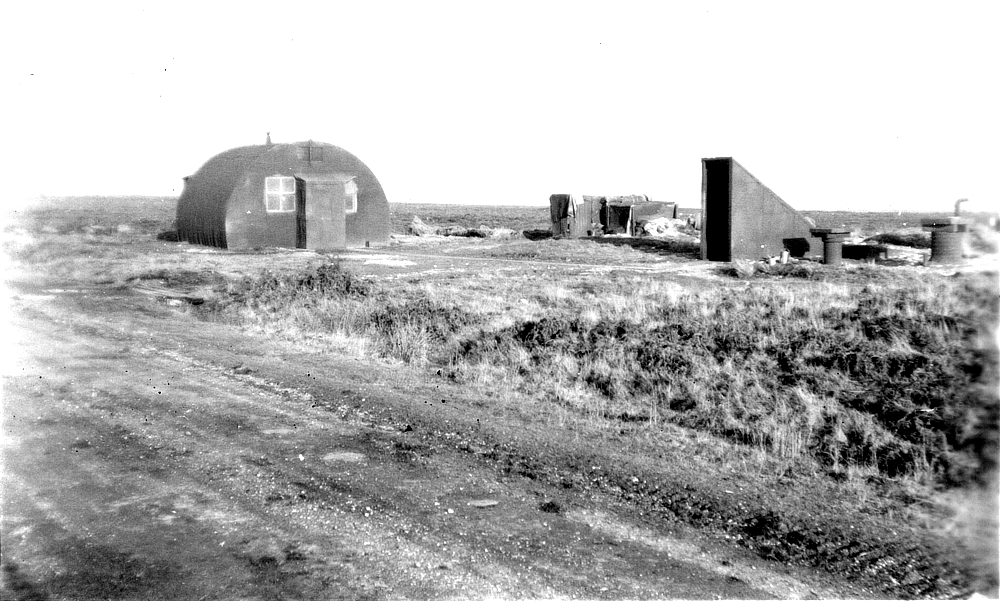

A Nissen Hut - Dad's would probably not have been as long as this one.

lights on and off in sections, kept records during raids, and prayed that

their shelter wouldn’t get a direct hit (while it was proof against

shrapnel and near-misses, a direct hit would have destroyed it, and anyone in it).

A Nissen Hut - Dad's would probably not have been as long as this one.

lights on and off in sections, kept records during raids, and prayed that

their shelter wouldn’t get a direct hit (while it was proof against

shrapnel and near-misses, a direct hit would have destroyed it, and anyone in it).

Next to the bunker was a Nissen Hut, where they spent their off-duty hours – catching up on sleep, cooking and eating, washing, etc. There was a table and two chairs in the middle of the hut to eat on during the day. Night raids could come at any time – they had to be on duty and alert all night. The gap between being instructed to turn on their lights, and the arrival of the first bombs, could be just a few minutes.

Their success was measured by how many bombs landed on their Q-Site (manned by just the two of them) versus how many landed on the real airfield (staffed by hundreds of servicemen and women).

While rummaging through some old family photo albums recently, I came across this photo, and realised that this could well be the Q-Site - there's a Nissen hut, and what looks like the entrance to an underground bunker, all in the middle of an expanse of empty heathland.

The Stories:

My Dad never talked about what he did in WW2, until a year or so before he died. He finally opened up over a pint in a local pub - I'd asked him what he did at RAF Warmwell, and he told me about the Q-Site. He said that they took their duties very seriously, and were always trying to think up new wheezes to make the Q-Site look more and more convincing. Some examples he told me:

- When they were warned of an imminent raid and had their lights switched on ready, they’d wait until they heard the bombers overhead, and then start turning their airfield lights off in sections, as if caught unawares, but they'd leave just one sector of the dummy airfield lights on, as if by panicked mistake. This would make it look more convincing, but still leave enough lights on to enable the Luftwaffe to proceed with their raid.

- On the dummy airfield they put a light hidden inside a wooden box with an open slit down one face. The light from the lamp would spread out in an arc over the ground from the slit, so that, from above, it would look like “bad black-out” – where black-out curtains hadn’t been pulled together properly.

- The scariest story he told me involved the tractor that they drove around the site to carry out repairs and maintenance. My Dad said he had this great idea. He got a couple of four-yard-long lengths of wood and attached these to the rear of the tractor, so that they stuck out, one on each side. He then attached a green lamp to the right-hand end, and a red lamp to the left-hand end. During a raid, instead of sheltering in the command bunker, he’d drive this tractor round the site, so that, from above, it would look like an aeroplane taxying! This just sounds ridiculously courageous, and made me realise how lucky I am to be alive.

Dad said that the worst part of the job wasn’t the night raids, but clearing up afterwards. In addition to the big High Explosive bombs, the Luftwaffe dropped dozens of small anti-personnel mines. After every raid, the whole site had to be swept to locate any unexploded bombs and these anti-personnel mines.

This involved bringing over a party of servicemen from the main airfield – they’d all form up in a long line abreast (my Dad included), a few yards apart, and walk slowly across the heather-covered heathland, with their eyes scanning the ground in front of them for mines. If they accidentally trod on a mine hidden in the heather, it would be bad news, and probably for the blokes on either side, as well. This was nerve-racking stuff.

If somebody spotted a mine, he’d shout out, and the line would come to a halt. A trench would be dug twenty yards from the mine, six feet long and a foot and a half deep. The Bomb Disposal expert would be called for – he’d gingerly tie a length of string around the mine, retreat to the trench, lie down and give the string a sharp yank. There’d be a loud bang, then the line of men would reform, and they’d start again. Hi-tech stuff.

Dad said that one day the two of them emerged at dawn from their night on duty in the bunker when there had been a heavy raid and walked over to their off-duty Nissen hut to relax and get some sleep. They noticed a large hole punched in the wall above the entrance door at one end of the hut. They carefully opened the door, and saw that one of their chairs had its back smashed in. With great care they looked under the table to discover to their horror an unexploded bomb sitting on the floor! This story is mentioned in the letter reproduced at the bottom of the “RAF Warmwell Q-Site” section above.

Photos

Each page contains about fifteen pictures totalling approx seven MB per page.

Conclusion

A brilliant day out, with perfect weather, and a marvellous route chosen by Berni. It was great to see my old stamping ground round the Isle of Wight and Poole Bay from the air. It was interesting to fly over where my dad served in WW2, although both the real and dummy airfields have long-since disappeared. A tasty burger at the very pleasant Compton Abbas airfield (where we also went for a short walk over the hillsides), and the opportunity to take in sights such as Stonehenge, Silbury Hill, and the famous Cerne Abbas Giant. Thanks to Berni for a marvellous experience.